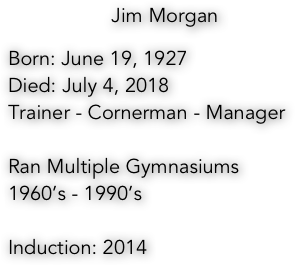

He was a father figure to certain fighters and the genuine article to others, yet both sides called him dad, a man they depended upon to subdue their racing emotions between rounds and send them back into the hellhole they had just left with their confidence restored and their determination rescued.

Some fighters said his presence alone after a deflating round was enough to restore their hope and desire, just moments removed in some cases from the edge of despair. He could be a beacon to a foundering ship, a first responder on the heels of disaster.

In the majority of cases however, Jim Morgan dealt with fighters trying to stay in control, trying to stem the flow of their adren- aline after sending their opponents staggering to the opposite corners. More often than not, his fighters were on the successful side of affairs.

“He was always clam, never raised his voice and he had a way of keeping you calm, too,’’ said Rick Folstad, a light welterweight originally from Little Falls who compiled a 20-2 record before becoming an award-winning sportswriter in Florida. “When I got back to the corner and saw Jim, I relaxed.’’

It was no different for Bob “Iceman” Coolidge, the Minneapolis middleweight, for whom Morgan was coach and cornerman throughout his entire amateur and professional career. “He was always cool and calm in that corner,’’ Coolidge agreed. “Never once raised his voice.’’

Whatever it was about Jim Morgan, it seemed to work. Coolidge finished his career with a 22-3-1 record.

“You know what it was,’’ added Coolidge. “Jim let you be yourself. He’d watch you hit the bag for a while at first, see what your tendencies and instincts were and then refine them. He didn’t try to change you.’’

It was more than just that.

“He was like a dad to me,’’ Coolidge added. “You know, I was just another member of that big family. I still call him dad when I see him.’’

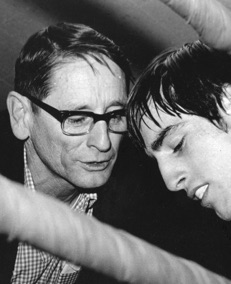

Jim and Olive Morgan are parents to 12 offspring, six boys and six girls. The family athleticism comes from both sides.

Jim was introduced to Olive Bastien by her brother Red. If the name has a familiar ring, it is because Red Bastien was a well

known combatant on the professional wrestling circuit and made the rounds in even tougher circuits at one time with Morgan, taking on all comers in saloon wrestling matches and the traveling carnivals and fairs.

Olive was from North Dakota, Jim from South Dakota. Their marriage was a union not only of the Dakotas but of athletic genes that produced champion prize fighters and wrestlers.

Olive laughed as she recalled her introduction to Jim. “I should have gotten a clue,’’ she said. “Our first date and he took me to a boxing match. The light should have gone on...but it has been a very interesting life, a very good life.’’

Indeed, the Morgan brothers – Jim and Olive’s six sons – have left their marks either in Big Ten and Olympic wrestling annals or on the boxing world at large: Glenn, Mike and Dan in the ring; John, Gordy and Marty on the mat. Yet even the family wrestlers put the gloves on at home as youngsters.

It began on the South Dakota prairie where Jim himself, like many Irish boys at the time, learned to box at the hand of their fathers and the parish priests. He grew up with 12 siblings, seven of them boys. If boxing was as natural as eggs at breakfast, wrestling was the bacon.

Jim Morgan brought with him the taciturn but disciplined manner found on the prairies of the West when he relocated to Minnesota.

“Dad was old school,’’ son Dan said. “He didn’t say much but

if he got mad, he’d put that old armlock on you and kick your butt. Wristlock Morgan. He used to take on all comers at those fairs. But the best thing was that he was a very good father. He taught us that whatever we did, to show up and do it with honor. Do your best. Mom and dad were both good parents.’’

Jim Morgan’s strength as a teacher, as a man who often took a stone of talent and polished it into a sparkling gem, is clearly reflected in the boys and young men he coached in the rings of the Golden Gloves, a program in which he produced and sent 20 or more Upper Midwest Champions to national tournaments including his own three sons who later became prominent professionals as well.

“Jim let you be yourself. He’d watch you hit the bag for a while at first, see what your tendencies and instincts were and then refine them. He didn’t try to change you.’’

Morgan had an ability to bring out the innate talent in fighters and mold them into boxers or punchers accordingly, instilling as well the confidence that comes from recognized skill and ability.

Confidence, Jim Morgan learned in his younger years, is best es- corted at times by sound judgment. He and Red Bastien usually

dominated the mats spread out on dance floors in saloons. It was outside those places afterward that demanded caution.

Take the former Persian Palms in downtown Minneapolis.

“It was one of the roughest places on Washington Avenue,’’

he recalled. “There was a place in back of the Palms where

we could park. We’d open the back door, look around and then run to the car. That was one tough neighborhood.’’

The warning signs were sometimes obvious. Opponents, defeated on the mat or not willing to engage there at all, would inform Morgan they would meet him outdoors when the saloon went dark, where God only knows what rules applied and what weapons might be involved.

The science of fighting does include some basic psychology at times in addition to a good jab and a straight right hand. Folstad recalled that Morgan knew how to make the best use of that minute between rounds while attending to a fighter’s physical or mental needs.

“You know a lot of people don’t understand that different things are flooding your thoughts between rounds, your mind is going in a thousand different directions,’’ Folstad said. “You need

to focus...on two or three things. You don’t need to hear very much, just a couple of things. Jim knew that. He could get you refocused.’’

Fighters had confidence in Morgan and consequently them- selves. “I was very close to my dad,’’ Folstad said. “He originally taught me to box. But Jim became like a second dad to me.’’

That’s what drew fighters to Morgan, and that’s what kept them interested in a sport that attracts many but converts few.

Coolidge showed up one day at Morgan’s gymnasium and informed him he wanted to box. Morgan put him to work on the bag so he could study what this newcomer had, his tendencies and instincts. He liked what he saw. It wasn’t until months later that he told Coolidge he had known from that very first visit he had the makings of a fighter.

“He told me he knew I wanted it, that I would make a good fighter,’’ Coolidge recalled, “because unlike a lot of other kids I showed up by myself, without my dad.’’

And fatherhood was Morgan’s primary domain. He knew what |it took to be a dad, when to take it easy and when to apply, as Dan recalled, the wristlock. Gentle persuasion at times, stern rhetoric at others. Perfect touches in the gym and especially between rounds on fight night.

Those attributes as much as any others are what Folstad recalls best three decades later.

“I was extremely happy to hear that Jim made it into Minnesota’s boxing hall of fame,’’ Folstad said.

So, too, are countless others, amateur and professional, who learned to box under Morgan, to punch, to compose themselves under pressure and, of course, to do whatever they did in life with honor.