You could find many of the best fighters in the Twin Cities and beyond at the time in a gymnasium on Hennepin Avenue, immediately above a jewelry store. It was the mecca of training facilities in the local fight game, and Jimmy Potts ran the place.

Drop in on no particular day and you might find Del or Glen Flanagan shadow boxing or keeping rhythm on a speed bag, providing the unmistakeable music associated with a boxing gymnasium, the rat-a-tat-tat of the bag on the platform. Danny Davis might be jumping rope in a corner, and Jackie Burke doing situps in the middle of a mat.

“It was on Seventh and Hennepin, right across from the news stand,’’ said former fighter and Hall of Fame inductee Jerry Slavin.

And anyone familiar with the place could always tell if Mel Brown were present, long before walking through the door.“You could hear the thump of the heavy bag when he hit it, from a block and a half away,’’ said Hall of Fame manager/trainer Bill Kaehn. “The guy could really hit.’’

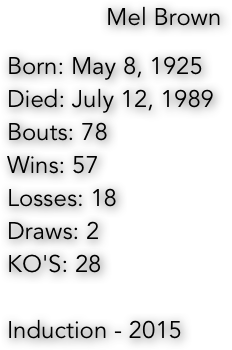

Milburn Tyler Brown, aka the Rondo Street Jinx, was a puncher of the highest order, a banger with sledgehammers for fists, as his record might indicate. More than half of his wins were by knockout.

“He was a rough, tough puncher,’’ said Kaehn. “He could destory an opponent with a couple of punches, but like most heavy punchers he caught plenty himself.’’ Nonetheless, Brown was stopped only twice in 78 fights, despite frequently fighting in an opponent’s home town. He was on the road so often that his Minnesota friends and fans rarely got to see him fight.

He fought the majority of his opponents at places round the globe, frequently in London and other English cities. He fought a number of times in the Netherlands, in Singapore and Belgium and also had fights in Denmark, Germany and France, a streak that kept him basically in Europe from 1951 to 1955. .

He fought frequently in New York, California and Massachusetts. His first three fights took place in St. Paul, Duluth and Minneapolis, his next eight in California. His last 22 fights were on the opponent’s home turf in Europe.

Every fighter, it seems, has an oddity or two on his record. In the case of Mel Brown and his brother Buzz, that oddity was Jackie Burke, a slick, smooth boxer who called Grand Rapids home and who seemed to have their number.

Burke won by unanimous decision over Mel for the Minnesota middleweight title on December 4, 1947 at the Minneapolis Auditorium. Twelve days later he knocked out Buzz Brown in the eighth round of a 10-round fight at the St. Paul Auditorium to keep that title.

Then, on January 8, 1948, Burke once again got the better of Mel Brown on points to win the vacant Minnesota light heavyweight title, thereby becoming the only fighter to hold both titles simultaneously. Slavin sparred at Potts Gym on several occasions with Brown. “He was a good fighter, really tough and rugged,’’ Slavin said.

Slavin can say that today although there might have been a time when he wouldn’t have offered a positive comment of any kind.

“We didn’t really like one another,’’ Slavin said. “I guess that was because whenever we worked out, we tried to kill one another.’’

There might have been other, competitive reasons, for their mutual dislike. On July 3, 1950, Brown scored a first-round knockout in Nottinghamshire, Nottingham, over one Paddy Slavin of Northern Ireland. When he returned to the United States and resumed training at Potts Gym, he had a comment for Jerry Slavin one afternoon.

“He told me that he had just knocked out my cousin,’’ Slavin recalled. Of course, the two were unrelated, but Jerry had a rejoinder nonetheless. “I told that him he might have knocked out that Slavin but that he couldn’t knock me out,’’ Slavin said.

A story in the Minneapolis Tribune on November 22, 1947 details a bout between Brown and Rueben Shank of Denver, Colorado. The article, by Lou Gelfand, carried these details:

Mel Brown, St. Paul middleweight, handed Rueben Shank of Denver, Colo., an unmerciful beating and then knocked him out in the eighth round of a scheduled 10-round main event bout in the Minneapolis Auditorium Friday night.

Shank collapsed in his corner after the fight and was carried to his dressing room on a stretcher. A short sidebar carried the additional information that Shank had suffered a concussion and said that he was retiring from the ring. The sidebar carried quotes from Shank saying that he was hurt and tired and didn’t want to fight again.

BoxRec carries the additional detail that Brown was close to death for 12 hours and that his Colorado and NBA licenses were revoked. He did not fight again for seven years and retired permanently after losing by TKO and then on points in two comeback fights. Brown himself retired after being stopped in a bout in the United Kingdom on June 9, 1955. After so many years of traveling, of fighting on the road, he returns now to a permanent spot, in the Minnesota Boxing Hall of Fame.